ELWHA RIVER — The Elwha watershed is booming with new life, after the world’s largest dam removal.

The first concrete went flying in September 2011, and Elwha Dam was out the following March. Glines Canyon Dam upriver tumbled for good in September 2014. Today the river roars through the tight rock canyon once plugged by Elwha Dam, and surges past the bald, rocky hill where the powerhouse stood. The hum of the generators is replaced by the river singing in full voice, shrugging off a century of confinement like it never happened. Nature’s resurgence is visible everywhere.

“Big things can happen if people persevere,” said Mike McHenry, biologist with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, which got the ball rolling on dam removal when it was still thought a crazy idea. “Back in 1990, you ask somebody in Anywhere, USA, about dam removal,” McHenry said, “they would have told you that you were nuts.”

Not anymore. Washington, still one of the most hydropower-rich states in the nation, is also today the world’s dam-busting pioneer.

PacifiCorp did the math on keeping the Condit Dam on the White Salmon River in Southwestern Washington and blew it up with one blast on Oct. 28, 2011.

It took an act of Congress in 1992 to finally free the Elwha, taking down the pair of dams that had blocked the 45-mile mountain river for a century.

The big idea in all three cases was to get rid of hydropower dams no longer worth their maintenance and repair. The dams also had no fish passage, as required by modern environmental laws. Dam removal is restoring 70 miles of spawning habitat in the Elwha.

The $325 million Elwha experiment remains the biggest dam removal project ever. With 83 percent of the Elwha watershed permanently protected in Olympic National Park, it offered a unique chance to start over.

It’s as if the whole watershed was waiting.

Scientists are amazed at the speed of change under way in the Elwha.

Elk stroll where there used to be reservoirs. Bigger, fatter birds are bearing more young, and moving in to stay. A young forest grows where there was blowing sand in the former reservoir lakebeds. Seeds tumble down the river’s coursing current. The big pulse of sediment trapped behind the dams is passed; the river has regained its luminous teal green color, and its channel is stabilizing.

Logs are tumbling and stacking in the river, building complex, braided channels, islands and jams.

And fish are booming back: More than 4,000 chinook spawners were counted above the former Elwha Dam the first season after it came down. Overall, fish populations are the highest in 30 years. And that’s before the first progeny of salmon and steelhead going to sea since dam removal come back this year.

Upper river

Big wood on the move

The dams blocked not only salmon heading upstream, but logs and root wads headed downstream. Especially behind Glines Canyon Dam, the upper of the two, wood that should have been distributed all throughout the river was stacked and stuck along the shores of Lake Mills. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe used a helicopter to pick up logs stuck against former lakeshores and pile them in log jams on the former lakebed to help new plantings get a better start. The logs shelter plants from wind, provide shade, accumulate organic matter and help hold moisture in the ground.

Middle river

The middle river was the realm between Glines Canyon Dam and the Elwha Dam, the lower of the two at 108 feet tall. No ocean-going fish lived here between the two dams for more than a century. Animals that normally fed on those fish were starved for nutrients from salmon. The river lacked the structure of gravel, sediment and big wood that an undammed river would have conveyed from the upper watershed and its banks.

Lower river's resurgence

The lower river was the only place available to salmon after 1910, when Elwha Dam was built five miles from the river mouth without fish passage. Entrepreneur Thomas Aldwell built Elwha Dam to generate hydropower to attract industry to the city of Port Angeles. Cheap hydropower helped jumpstart the economy on the Olympic Peninsula. But it came at a price: Anadromous fish populations in the river declined by 98 percent overall during the past century.

At the mouth of the Elwha

After the dam

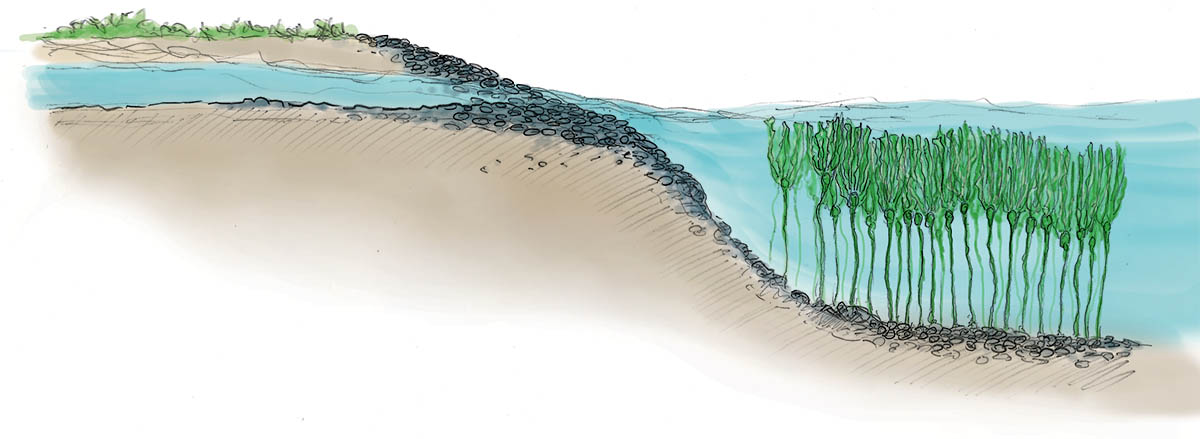

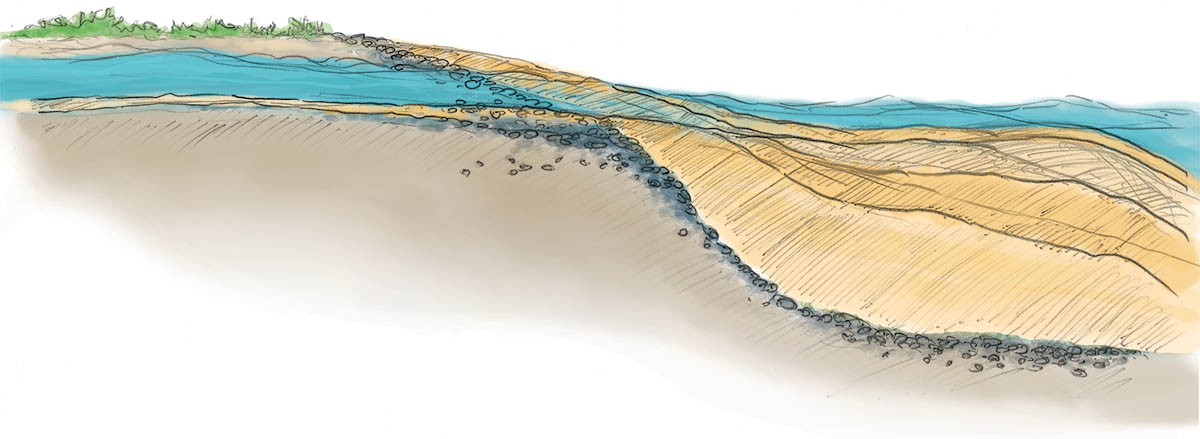

Unplugging the Elwha birthed Washington's newest beach. The river built it grain by grain, by moving a massive load of sediment from behind the dams. The vast majority of the sediment released from the reservoirs wound up in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where winds, tides and the prevailing currents carried it mostly east of the river mouth. About 4.6 million cubic yards of sand and gravel deposited at the river delta, with drifts piled more than 30 feet deep on the bottom of the nearshore, below the tide line. Most of the mud was carried far away on the current.

Originally published February 13, 2016

Lynda V. Mapes: 206-464-2515 or lmapes@seattletimes.com