First Foods

How Native people are revitalizing the natural nourishment of the Pacific Northwest

Seattle Times staff

Published July 10, 2022

Five or six generations ago, Native people of this region ate a complex diet that changed with the seasons. Called First Foods, these are the staples they always relied on.

Today a movement in tribal communities is promoting First Foods traditions and decolonizing Native diets and taste buds to restore bodily, cultural and spiritual health.

“It was promised we would have access to these things,” said Valerie Segrest, a Muckleshoot Indian Tribe member and Native foods educator. Under the treaties of Medicine Creek and Point Elliott, the Muckleshoot forever reserved hunting, gathering and fishing rights beyond their reservation at Auburn.

“It was always based on food,” she said of the treaties. “That is what we ceded all our lands for. It was important to us because in our creation stories, our foods teach us who we are. If we didn’t have access to our foods, we would not be a Native person.”

This spring, The Seattle Times traveled along with Native people gathering their First Foods, to document these cultural practices, their meaning and centrality to the treaty promises.

“People have to understand why we reserved the rights we did, why our people did that,” said Shannon Wheeler, vice chairman of the Nez Perce Tribe.

“It is because of the unwritten laws we have, our obligation to the land and its inhabitants, and our obligation to the First Foods and how we live with the land and interact with the land and treat the land. It is our oldest law. Before the treaty. It is what the treaty was meant to capture.”

Segrest passed out buckets, gloves and scissors to her daughters, and the three started clipping. They took the top several inches of the plant and left the rest to thrive. They spread out their effort so no part of the patch was depleted.

“It is easy to forget what time it is,” Segrest said as they worked, and it was true. The rhythms of the natural world — the seasons, the native plants and their harvest time — reset the usual mainstream frenetic clock.

“We are not seasonally attuned anymore,” Segrest said. “For the first time in human history, we are so disconnected.”

Spring isn’t supposed to be just months on a calendar, Segrest said. It is the time of cleavers, claytonia and nettles bursting through soil damp with rain. These are among the first fresh green foods of the year, and they deliver the energy to live the dreams from the time of rest and renewal that is winter, Segrest said.

The nettle patches here are among her favorites.

“They call to us to get out here; I crave the feeling of stinging on my fingers,” Segrest said. The sting comes from the plant’s tiny hairs, which are easily removed with cooking. Steeped into a tea, eaten steamed or blanched, nettles deliver more iron than spinach, and a healthy punch of magnesium, calcium and phosphorus. That is typical of First Foods, Segrest said. They are very nutrient-dense.

In her culture, nettles and other plants are teachers, and they like to be visited.

The modern world has set up divisions and barriers from these companions in what used to be daily life. The skills to gather and prepare these foods and even a taste for their subtle flavors, have to be recultivated, brought back, Segrest said.

“These are the foods with which our cultures developed over thousands of years.”

“Every time we go out, it’s an exercise in our treaty right, being in our usual and accustomed areas, engaging our culture and spiritual practices,” said Willard Bill Jr., cultural director for the Muckleshoot, who skippered the tribe’s canoe Eagle Spirit over from Redondo for the feast.

“It’s critical for our treaty, to come and do this, traveling like our ancestors did, to come harvest these First Foods, retrain our palates. People 100 years ago were not overweight. They did not have diabetes. It was the first Paleo Diet.”

This is a way of being with their ancestors, said Billie Jo Bray, a member of the San Poil band of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. “I feel that connection when I come out here,” Bray said, “I feel that we are still here. It’s that way of life of our ancestors that they passed on to us.”

Somewhere across the prairie, a digger was singing as she worked.

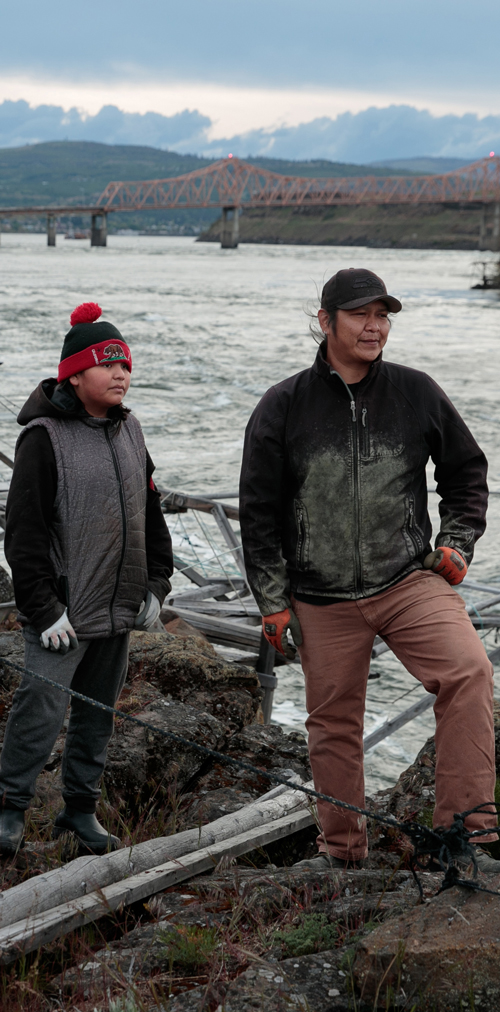

Even into the 1850s, after the horrific waves of diseases, the river still supported as many as 5,000 Indian fishers at about 480 sites at Celilo, according to historian Katrine Barber in her book “Death of Celilo Falls.”

That ended in 1957 with the building of The Dalles Dam, which drowned the falls and destroyed the fishery at Celilo.

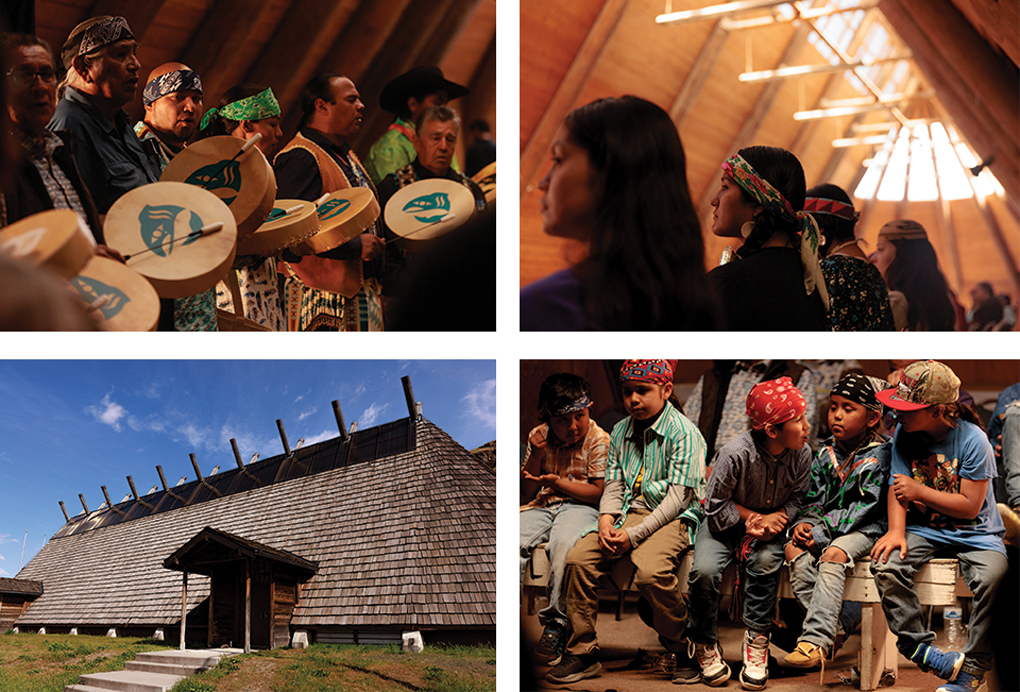

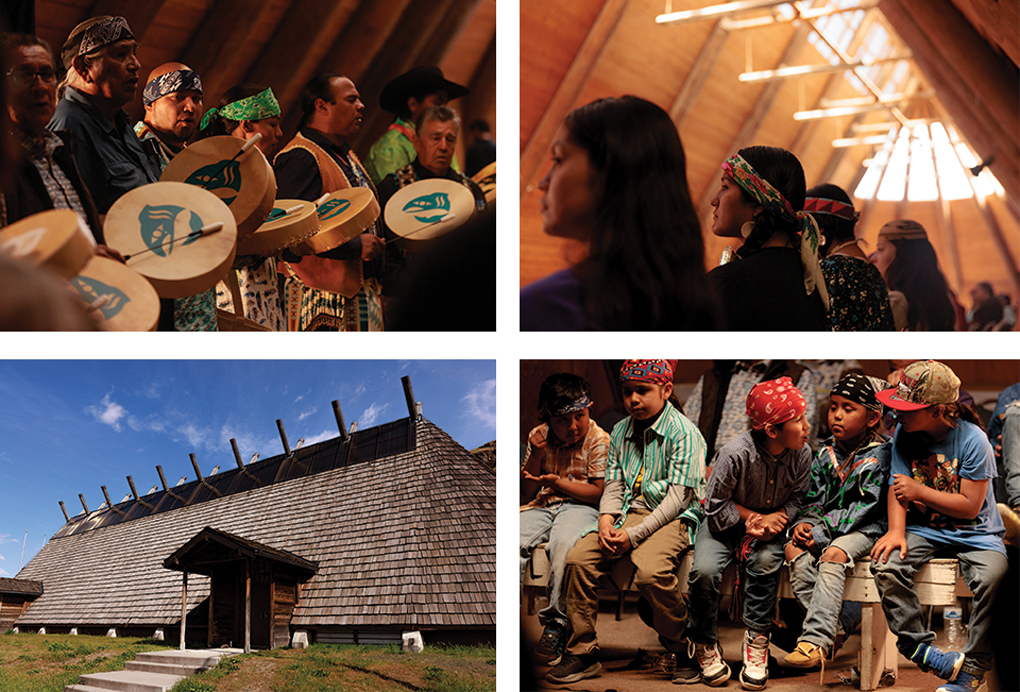

And so the mood at a gathering of salmon tribes at the Celilo longhouse on a recent spring day was somber. Instead of coming together for a harvest, as they once would have this time of year, the purpose was to unite around restoring what has been lost.

Amid the songs and oratory, the work of the cooks went on, as it always has and as it must, said Melinda Jim of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation.

At 72, she had been up since 6 a.m. for a day on her feet, preparing a feast for the longhouse gathering of salmon nations. Cooking for tribal community gatherings is her art and her work. She has 27 aprons, some from her mother and grandmother, and a lifetime of cooking experience. Jim commands a kitchen.

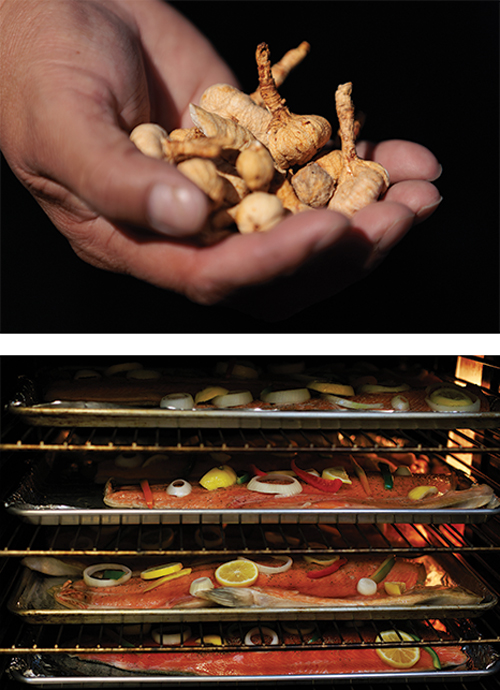

Stirring this, checking that, she directed helpers setting out the foods for the feast: There was biscuitroot, bitterroot, oven-roasted deer, baked salmon and huckleberries preserved last summer.

“It keeps us healthy,” Jim said of these First Foods. “We don’t get sick as much when we eat our own diet.”

Frances Charles, chairwoman of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, was honored in the longhouse ceremony at Celilo for her leadership in dam removal on the Elwha River, the largest ever dam removal project in the world. It was the work, she stressed, of elders and tribal leaders before her that also helped bring the $325 million federal project to completion in 2014.

“It took 100 years, but we saw those tears of joy in the elders’ faces,” Charles said.

That success is inspiring for Yurok tribal member Amy Cordalis, attorney for the tribe, as she helps lead the removal of four dams on the Klamath River in Oregon, expected to begin in 2024, for salmon recovery. The treaties demand it, Cordalis said.

“Treaties are the supreme law of the land. In light of that, how is it that these populations of salmon in the Columbia River and the Klamath River are down to single-digit percentages of their historical size?

“This will not stand. The treaty right was not given to us, it is a reservation of an inherent right that the tribes got from the Creator. We reserved that right in the treaties. And that absolutely meant having salmon in the river.”

In Washington, the region is considering dam removal on the Lower Snake River. A draft report on replacing benefits of the dams is out for public comment, with a final report and recommendation expected from U.S. Sen. Patty Murray and Gov. Jay Inslee later this summer. Among their considerations is the impact on tribal treaty rights and cultures from the loss of salmon. Also to be weighed: the legal obligation to protect 13 runs of salmon and steelhead listed under the Endangered Species Act; the feasibility and cost of replacing hydropower from the dams, which produce enough electricity to power a city the size of Seattle; providing alternatives to transportation on the Lower Snake through locks at the dams from Pasco, to Lewiston, Idaho; and reworking infrastructure that provides irrigation for growers from the reservoir behind Ice Harbor Dam.

The presence of the salmon’s absence is overwhelming, and is a reality that must be reversed with dam removal on the Lower Snake River, said Alyssa Macy, CEO of the Washington Environmental Council and Washington Conservation Voters and a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation. Living cultures require living salmon.

“It was promised we would have access to these things,” said Valerie Segrest, a Muckleshoot Indian Tribe member and Native foods educator. Under the treaties of Medicine Creek and Point Elliott, the Muckleshoot forever reserved hunting, gathering and fishing rights beyond their reservation at Auburn.

“It was always based on food,” she said of the treaties. “That is what we ceded all our lands for. It was important to us because in our creation stories, our foods teach us who we are. If we didn’t have access to our foods, we would not be a Native person.”

This spring, The Seattle Times traveled along with Native people gathering their First Foods, to document these cultural practices, their meaning and centrality to the treaty promises.

“People have to understand why we reserved the rights we did, why our people did that,” said Shannon Wheeler, vice chairman of the Nez Perce Tribe.

“It is because of the unwritten laws we have, our obligation to the land and its inhabitants, and our obligation to the First Foods and how we live with the land and interact with the land and treat the land. It is our oldest law. Before the treaty. It is what the treaty was meant to capture.”

Segrest passed out buckets, gloves and scissors to her daughters, and the three started clipping. They took the top several inches of the plant and left the rest to thrive. They spread out their effort so no part of the patch was depleted.

“It is easy to forget what time it is,” Segrest said as they worked, and it was true. The rhythms of the natural world — the seasons, the native plants and their harvest time — reset the usual mainstream frenetic clock.

“We are not seasonally attuned anymore,” Segrest said. “For the first time in human history, we are so disconnected.”

Spring isn’t supposed to be just months on a calendar, Segrest said. It is the time of cleavers, claytonia and nettles bursting through soil damp with rain. These are among the first fresh green foods of the year, and they deliver the energy to live the dreams from the time of rest and renewal that is winter, Segrest said.

The nettle patches here are among her favorites.

“They call to us to get out here; I crave the feeling of stinging on my fingers,” Segrest said. The sting comes from the plant’s tiny hairs, which are easily removed with cooking. Steeped into a tea, eaten steamed or blanched, nettles deliver more iron than spinach, and a healthy punch of magnesium, calcium and phosphorus. That is typical of First Foods, Segrest said. They are very nutrient-dense.

In her culture, nettles and other plants are teachers, and they like to be visited.

The modern world has set up divisions and barriers from these companions in what used to be daily life. The skills to gather and prepare these foods and even a taste for their subtle flavors, have to be recultivated, brought back, Segrest said.

“These are the foods with which our cultures developed over thousands of years.”

“Every time we go out, it’s an exercise in our treaty right, being in our usual and accustomed areas, engaging our culture and spiritual practices,” said Willard Bill Jr., cultural director for the Muckleshoot, who skippered the tribe’s canoe Eagle Spirit over from Redondo for the feast.

“It’s critical for our treaty, to come and do this, traveling like our ancestors did, to come harvest these First Foods, retrain our palates. People 100 years ago were not overweight. They did not have diabetes. It was the first Paleo Diet.”

This is a way of being with their ancestors, said Billie Jo Bray, a member of the San Poil band of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. “I feel that connection when I come out here,” Bray said, “I feel that we are still here. It’s that way of life of our ancestors that they passed on to us.”

Somewhere across the prairie, a digger was singing as she worked.

Even into the 1850s, after the horrific waves of diseases, the river still supported as many as 5,000 Indian fishers at about 480 sites at Celilo, according to historian Katrine Barber in her book “Death of Celilo Falls.”

That ended in 1957 with the building of The Dalles Dam, which drowned the falls and destroyed the fishery at Celilo.

And so the mood at a gathering of salmon tribes at the Celilo longhouse on a recent spring day was somber. Instead of coming together for a harvest, as they once would have this time of year, the purpose was to unite around restoring what has been lost.

Amid the songs and oratory, the work of the cooks went on, as it always has and as it must, said Melinda Jim of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation.

At 72, she had been up since 6 a.m. for a day on her feet, preparing a feast for the longhouse gathering of salmon nations. Cooking for tribal community gatherings is her art and her work. She has 27 aprons, some from her mother and grandmother, and a lifetime of cooking experience. Jim commands a kitchen.

Stirring this, checking that, she directed helpers setting out the foods for the feast: There was biscuitroot, bitterroot, oven-roasted deer, baked salmon and huckleberries preserved last summer.

“It keeps us healthy,” Jim said of these First Foods. “We don’t get sick as much when we eat our own diet.”

Frances Charles, chairwoman of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, was honored in the longhouse ceremony at Celilo for her leadership in dam removal on the Elwha River, the largest ever dam removal project in the world. It was the work, she stressed, of elders and tribal leaders before her that also helped bring the $325 million federal project to completion in 2014.

“It took 100 years, but we saw those tears of joy in the elders’ faces,” Charles said.

That success is inspiring for Yurok tribal member Amy Cordalis, attorney for the tribe, as she helps lead the removal of four dams on the Klamath River in Oregon, expected to begin in 2024, for salmon recovery. The treaties demand it, Cordalis said.

“Treaties are the supreme law of the land. In light of that, how is it that these populations of salmon in the Columbia River and the Klamath River are down to single-digit percentages of their historical size?

“This will not stand. The treaty right was not given to us, it is a reservation of an inherent right that the tribes got from the Creator. We reserved that right in the treaties. And that absolutely meant having salmon in the river.”

In Washington, the region is considering dam removal on the Lower Snake River. A draft report on replacing benefits of the dams is out for public comment, with a final report and recommendation expected from U.S. Sen. Patty Murray and Gov. Jay Inslee later this summer. Among their considerations is the impact on tribal treaty rights and cultures from the loss of salmon. Also to be weighed: the legal obligation to protect 13 runs of salmon and steelhead listed under the Endangered Species Act; the feasibility and cost of replacing hydropower from the dams, which produce enough electricity to power a city the size of Seattle; providing alternatives to transportation on the Lower Snake through locks at the dams from Pasco, to Lewiston, Idaho; and reworking infrastructure that provides irrigation for growers from the reservoir behind Ice Harbor Dam.

The presence of the salmon’s absence is overwhelming, and is a reality that must be reversed with dam removal on the Lower Snake River, said Alyssa Macy, CEO of the Washington Environmental Council and Washington Conservation Voters and a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation. Living cultures require living salmon.