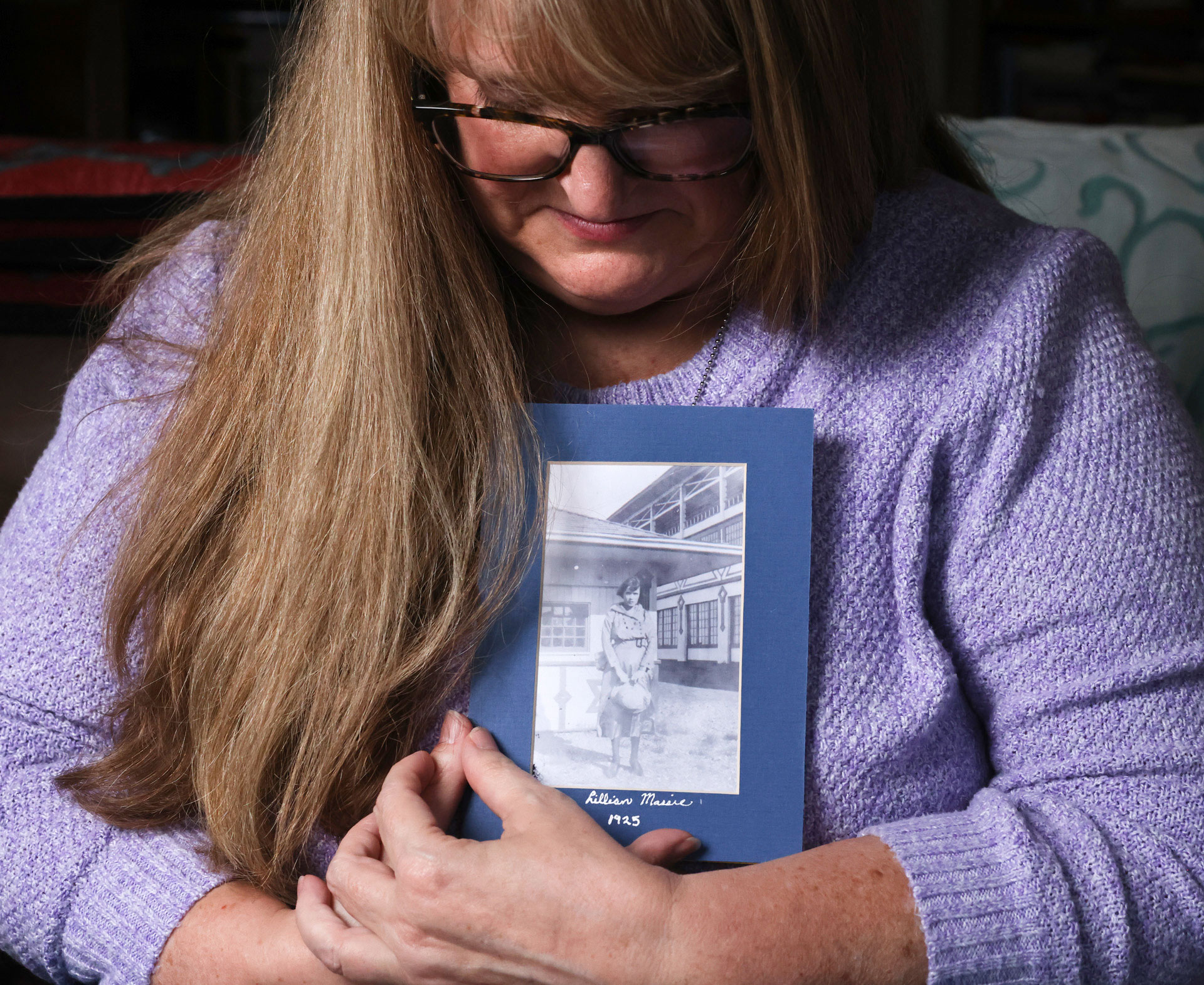

Carrie Davidson, Lillian’s great-granddaughter, runs her hands over the faded photograph as she sits on a sofa in her Auburn home. She keeps it in a plain wooden box along with pine cones and a broken piece of skylight glass from the crumbling Northern State Hospital campus, where she believes her great-grandmother’s remains could be buried.

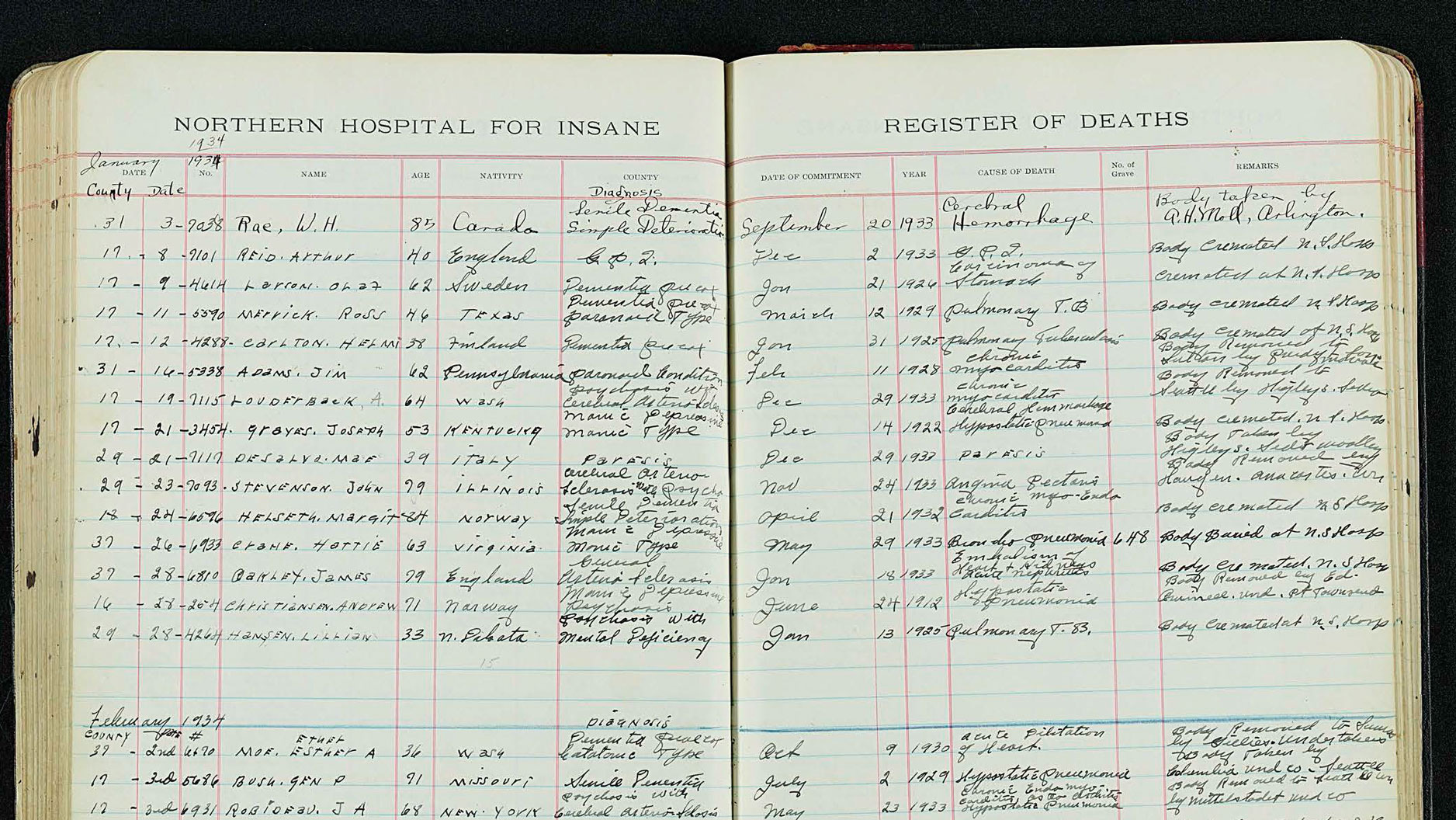

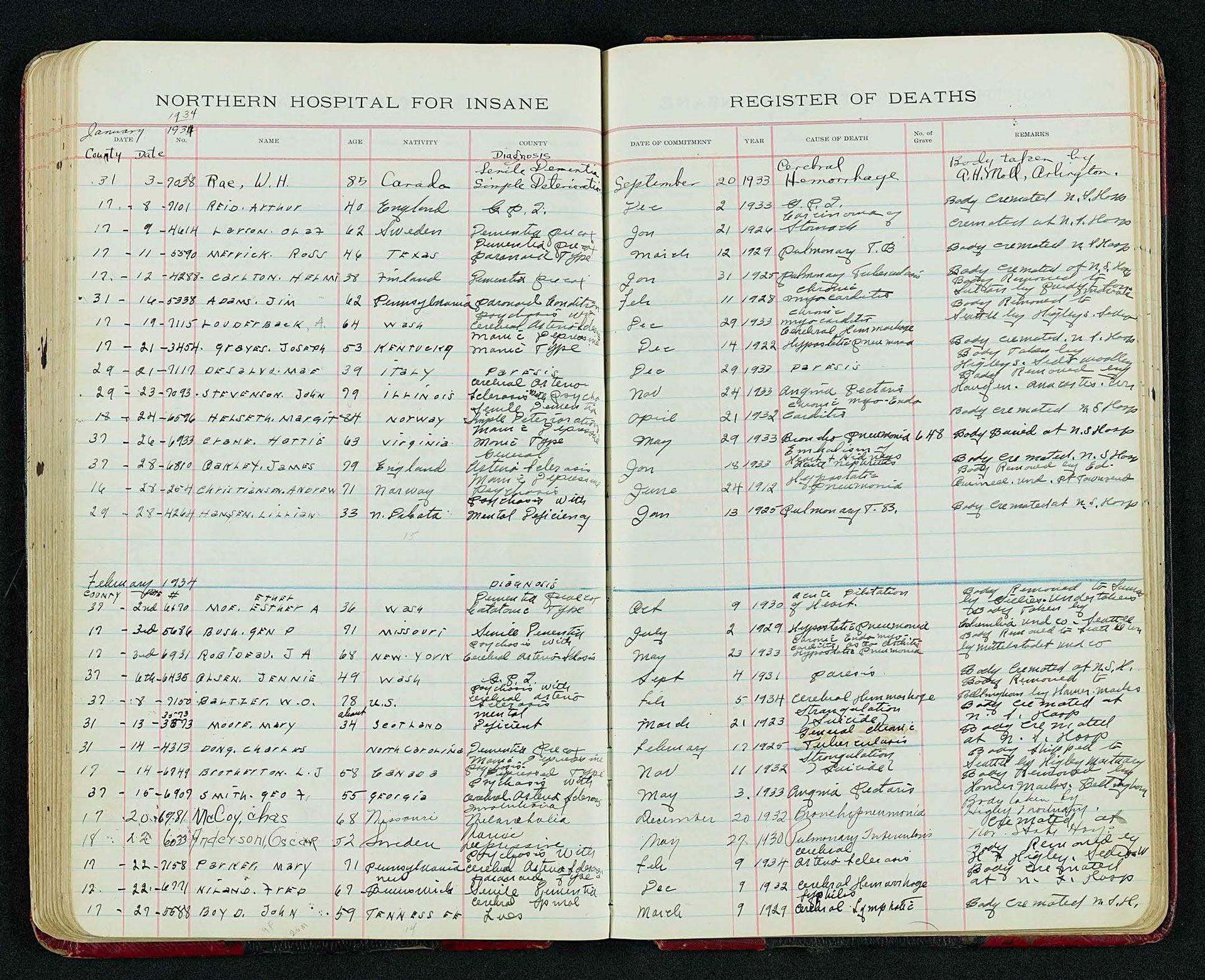

Northern State Hospital took in tens of thousands of people like Lillian, most from the Seattle area. Today, there’s scant evidence these patients ever existed. But as the 50-year anniversary of Northern State’s closure approaches this summer, family members and neighbors of the abandoned institution are fighting to recover them.

At her Auburn home, Carrie Davidson holds a photo of her great-grandmother, Lillian. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

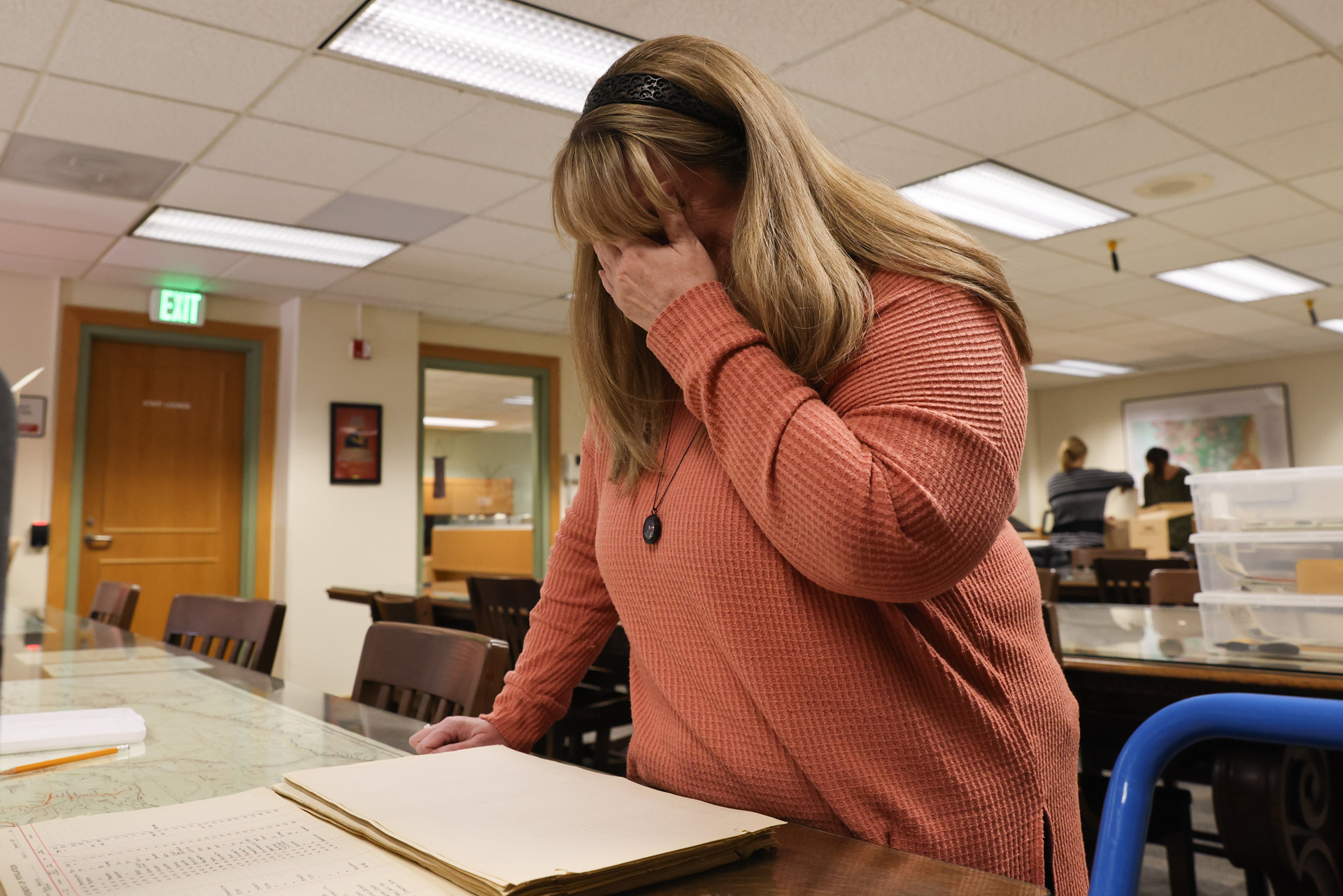

Davidson has chased after every scrap of information she can about her great-grandmother’s life. She negotiated with Canadian archivists, consulted a lawyer on how to obtain 100-year-old court records and even hired a medium to divine the location of Lillian’s grave.

Shame around her great-grandmother’s story snuffed her out from family history, and Davidson believes it haunted her grandfather for the rest of his life, pushed him to drink. Davidson’s grandfather never knew his institutionalized mother and was adopted shortly after his birth.

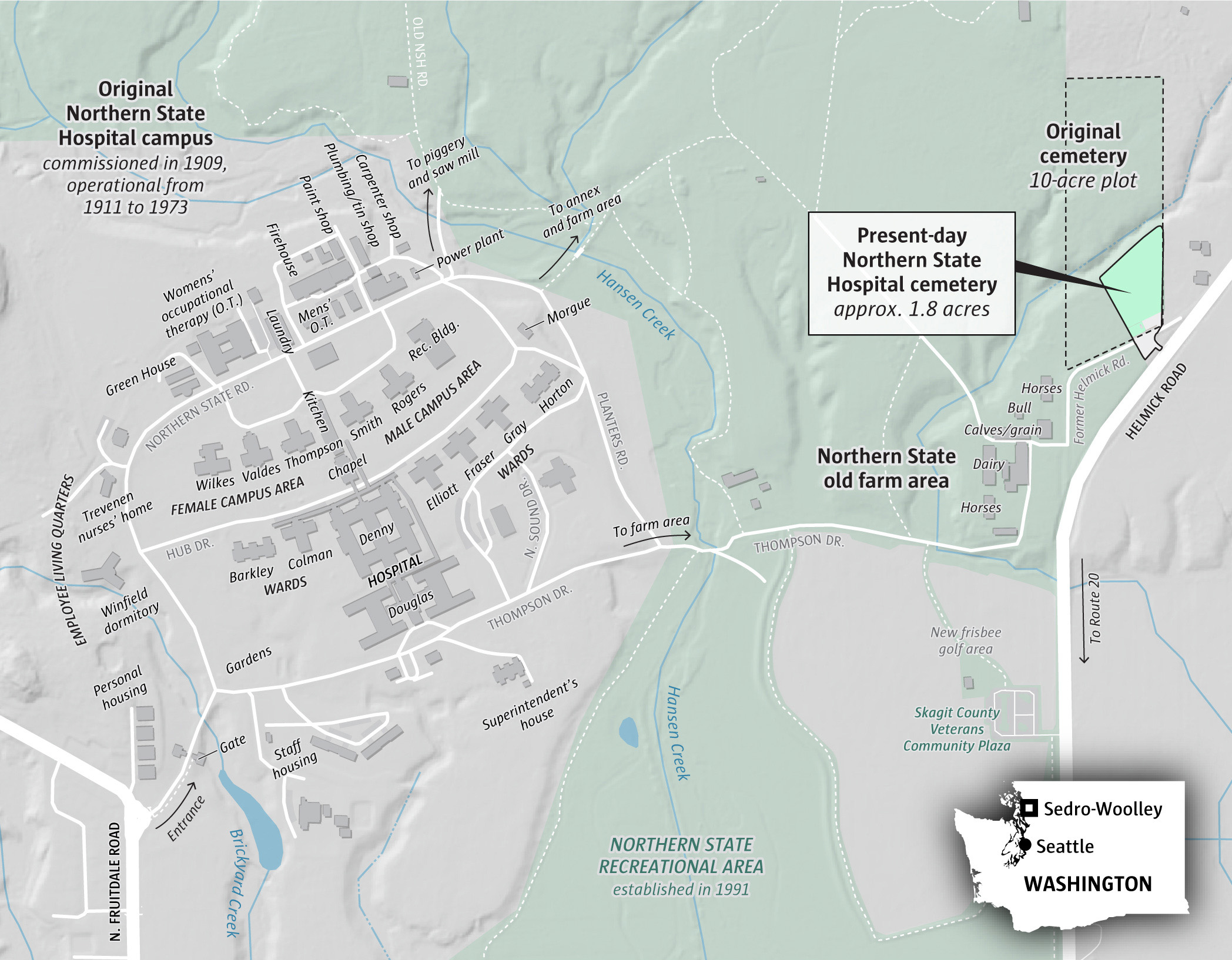

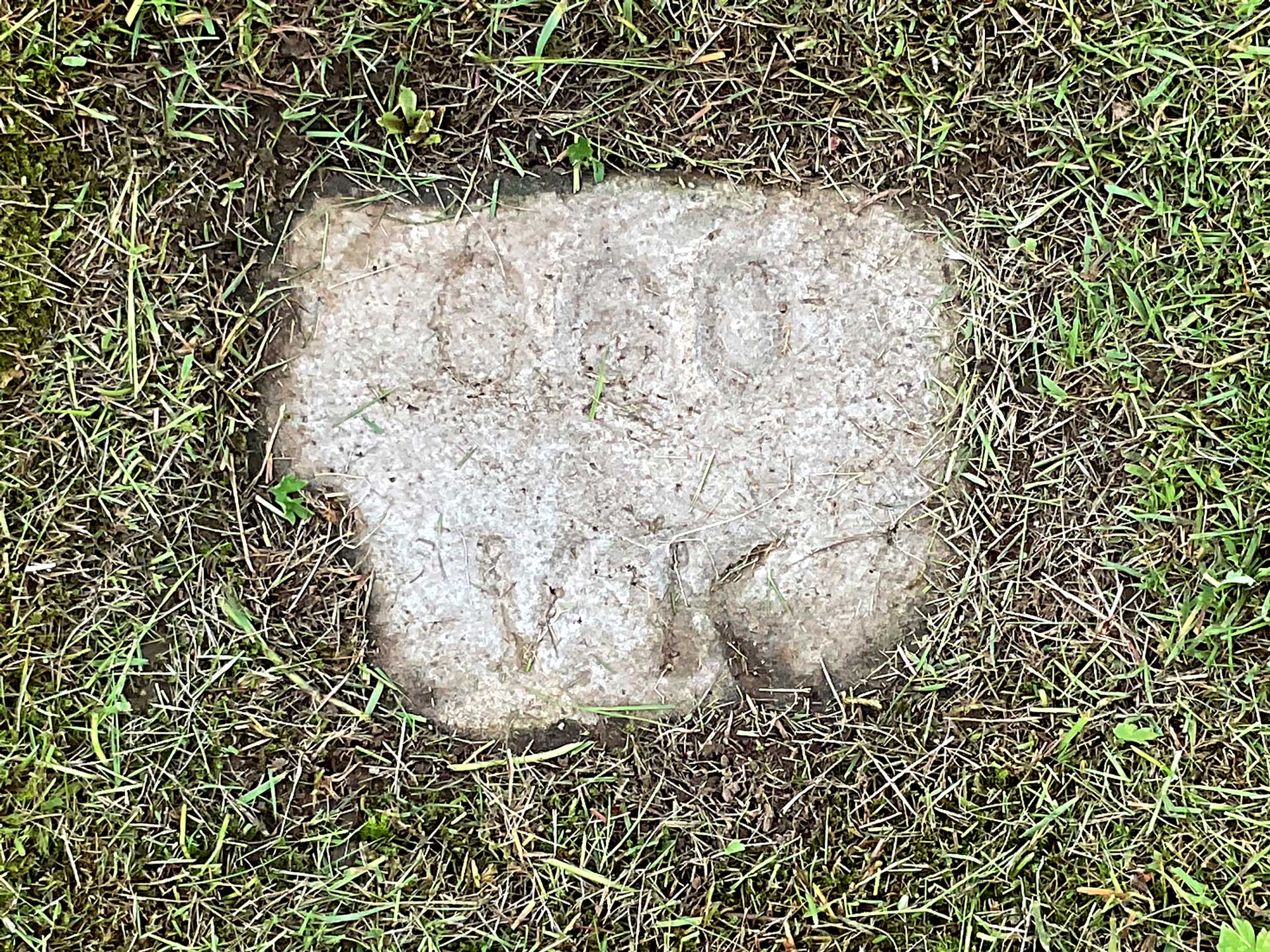

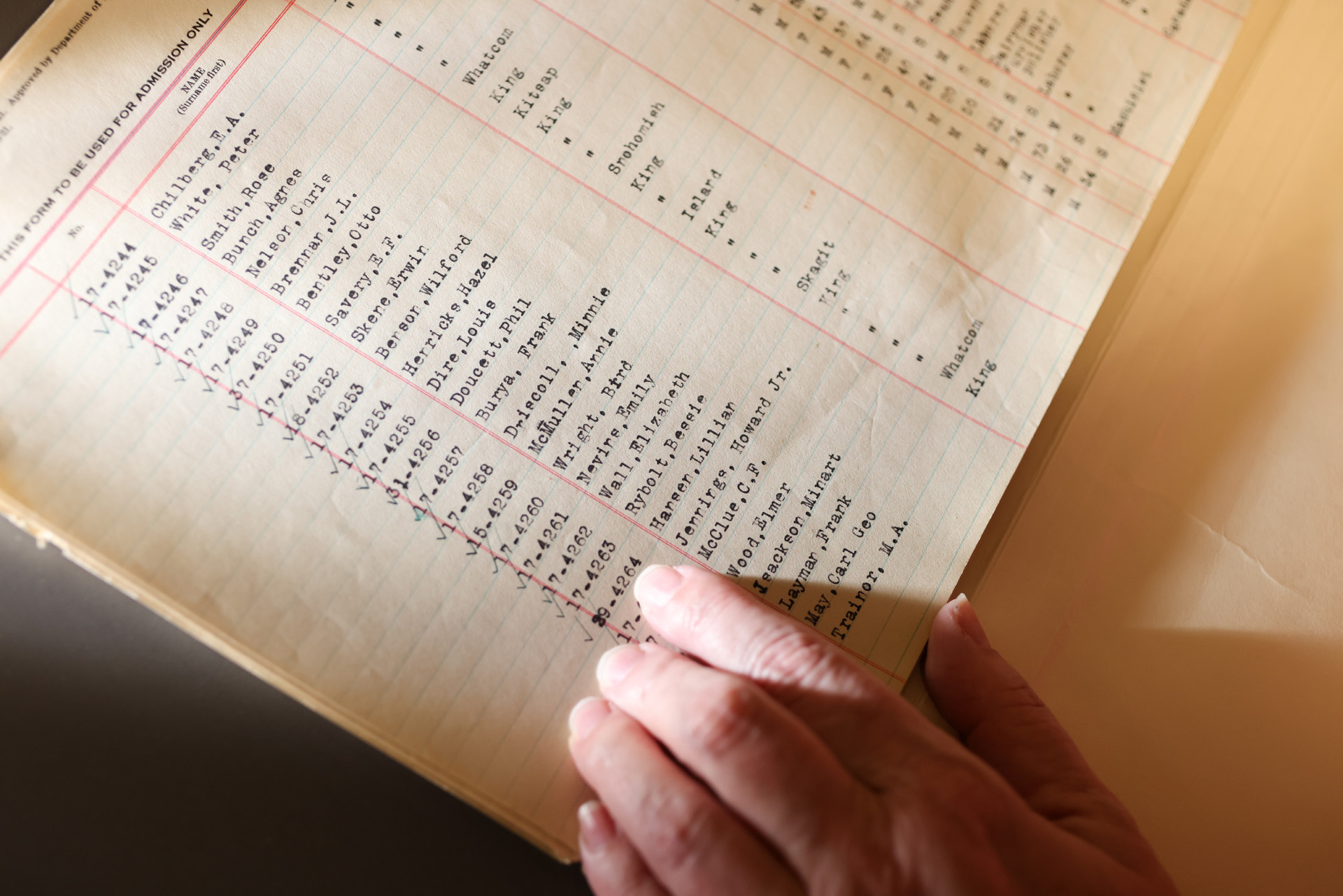

Many descendants like Davidson have not been able to find out what happened to their relatives or even where they were buried. Patient records were sealed off. Initials and numbers stand in for names on the hospital cemetery headstones, most now sunk beneath the mud. More than 1,600 patients are believed to be buried on the campus or elsewhere in the valley — close to 900 of them cremated and interred in metal food cans.

An aerial view of Northern State Hospital, which closed in 1973. The Port of Skagit took ownership of the property in 2018 and has since opened parts of it to the public. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

The state lost patients in other ways too. Austerity-driven political decisions pushed Northern State patients into group homes and onto the street when the hospital closed in 1973. The legacy of those policies shapes the system today, as people with serious mental illnesses ricochet among Seattle streets, jail and the few remaining state psychiatric beds in Western Washington.

Much of the country is now considering a push for more psychiatric care to get people off the street, such as California’s and New York City’s plans to expand involuntary treatment. Some fed up with the current mental health system look to places like Northern State with nostalgia. Many others see institutions as prisons for people with mental illnesses.

Between the two narratives are missing graves and ghost stories.

WATCH: Finding Lillian

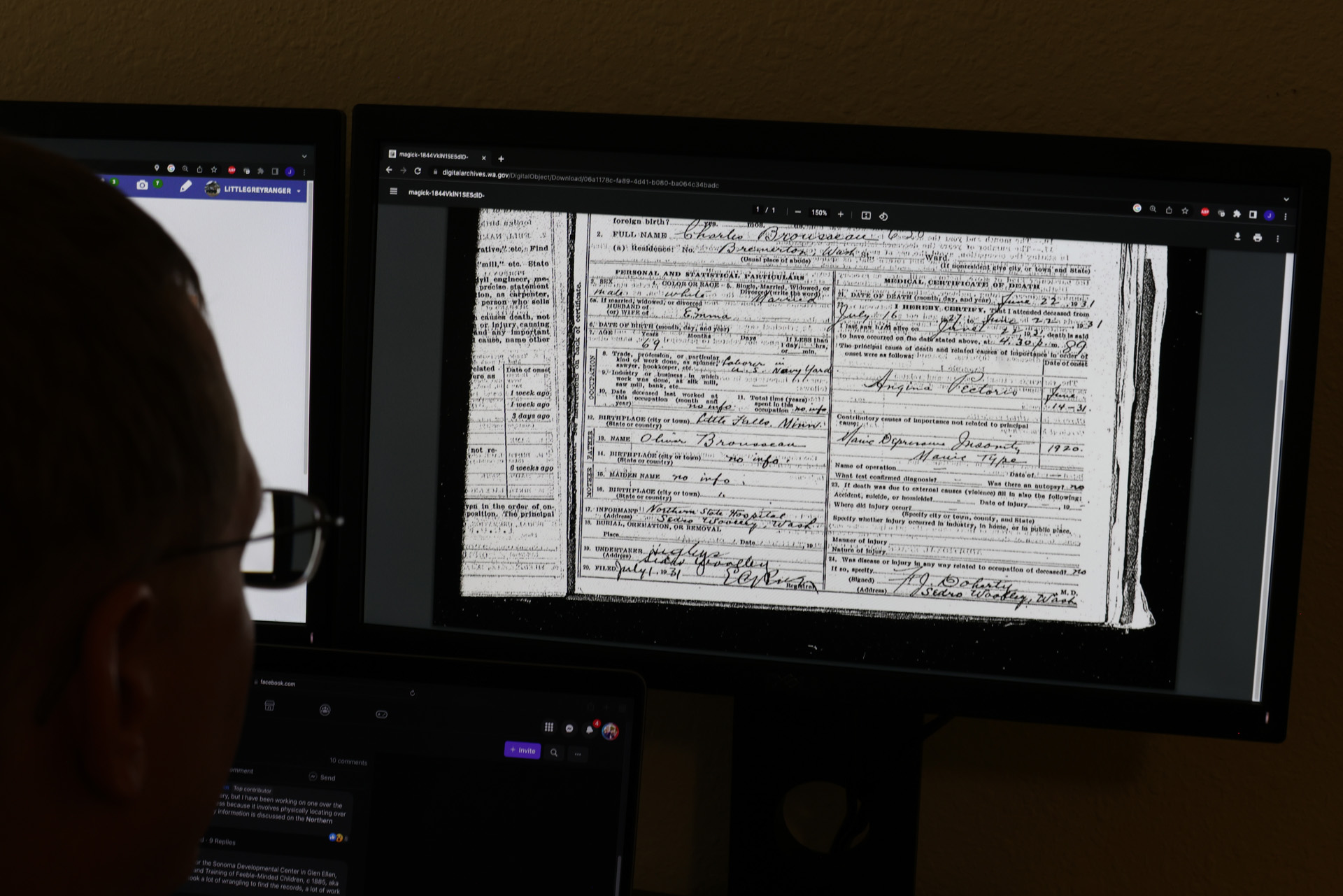

The Seattle Times successfully pushed to uncover long-sealed archival records and digitized them for the public. (Washington State Archives)

Davidson didn’t even know her great-grandmother’s name until her grandmother’s aging mind revealed it. She scoured genealogy websites and found a death record naming Northern State Hospital in Sedro-Woolley, a small farming town at the base of the Cascade Mountains. She’d never heard of the hospital.

Davidson pleaded with the state for more information and had just about given up looking for her great-grandmother’s Northern State records when she found a Facebook group in the summer of 2020 dedicated to the hospital and its cemetery.

“My great-grandmother was a patient who died at Northern State in 1934,” she wrote to the group. “Is there any way to find out if she’s buried in the cemetery?”

More than a year later, she got a response.

“I have been working on the burial records and uncovering grave markers for about a year now,” the message read. “What information do you have about her? I will see what I can find.”

II.

“Nope, nope, but if that’s the edge of one …”

John Horne sinks a three-foot steel rod into the soft earth of the Northern State Hospital cemetery. A couple of inches down, it makes a sharp cunk, the sound of metal on rock.

John Horne searches for grave markers at the Northern State Hospital cemetery. He believes at least 200 patients were buried outside the current cemetery’s borders. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times, 2022)

He prods again and with a little more pressure, it scrapes past something small. Gravel, not a headstone. Not what Horne is looking for.

He steps a foot away and tries again.

Cunk.

“Oh, there we go. There’s one.” Another push with the rod. Cunk.

Occasionally, a visitor to the Northern State Hospital cemetery — an oddly shaped plot dotted by mole hills — will spot a lanky man with a nut and bolt earring digging where the graves ought to be.

Not technically digging, Horne says, because digging up bodies in cemeteries is not allowed without a permit by the state, which has largely ignored the little cemetery.

Rather, he’s simply doing what he calls edging, trimming the grass and brushing away the soil that covers the headstones closest to the surface. For any deeper headstones he finds, Horne has a system of color-coded flags, orange ground paint and an herbicide to mark the grass when the paint gets washed away by rain or flooding.

Horne searches for grave markers at the Northern State Hospital cemetery. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times, 2022)

Horne monitors the Facebook groups he runs from his home. He helps connect relatives to information about loved ones who were admitted to Northern State Hospital through documents and information gleaned from the grave markers he unearths. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

Horne uses a bamboo skewer to clean a grave marker, revealing its number. Every winter, the cemetery ground sucks many markers back down beneath the mud. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times, 2022)

The muddy 1.8-acre cemetery is more a monument to erasure than remembering. Countless families have made the pilgrimage here over the last half-century, looking for clues about their forgotten relatives. Before Horne started poking around three years ago, the waterlogged cemetery had swallowed nearly all of its headstones under the mud, the identities of patients lost to history.

Today, Horne has uncovered 200 of those headstones and identified 300 more beneath the surface. He matches initials to burial records scavenged from the bottom of a file cabinet on the hospital campus, then uploads the information to FindAGrave.com and Facebook, where more than 1,800 people follow his work. That’s how he met Davidson.

Horne can cite a few reasons why he does this. The first is because of the way his mind works: Horne has attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and there’s nothing his brain loves more than fixing something broken or solving a mystery. He can spend entire days, from morning until dusk, working in the cemetery with only cans of energy drinks to keep him going.

Horne sees the possibility of a different world in Northern State’s past, with patients who milked cows from the hospital dairy herd and pickled onions from the institution’s farm. He used to work as a chemical dependency counselor on the Northern State campus, where he admitted patients into a treatment center. There he saw the same people over and over again, cycling through jail, emergency rooms and his office. He watched many die in that shuffle, having found no safe, long-term place to heal.

In some moments, Horne would look out his office window at the crumbling hospital buildings and imagine what they were like in their heyday. Would life be different for his patients if Northern State never closed?

Horne looks through the windows of the Gray building, also known as Ward 5, in Sedro-Woolley. Horne is a board member of the Sedro-Woolley Museum who researches Northern State Hospital’s history and burials. He hopes the buildings can be preserved. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

Horne walks around a former men’s ward at the Northern State Hospital grounds. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

Horne examines calipers found on an old operating table in the warehouse of the Sedro-Woolley Museum. (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)

Horne got so burned out that he quit his job last year. But he continues to work on the cemetery, even though the more he does, the less the place makes sense. Most of the headstones aren’t buried in order. The rows don’t line up. And recently, Horne discovered even more headstones and suspected graves outside the cemetery fence, near the parking lot.

He has a theory as to why. Old documents describe the cemetery as a 10-acre plot of the hospital’s best farmland. Now, it’s a two-acre corner near the road. Rumors circulated in Sedro-Woolley for years about people stealing the headstones or mowing them over and piling them up by the fence. One man even found a patient’s headstone propping up the corner of a cabin on his property. A former Northern State campus worker showed Horne a faded Polaroid of headstones piled in a shallow hole.

Based on these discoveries, Horne believes what’s now labeled as the cemetery is actually a small portion of what it once was. The bodies of at least 200 patients, according to Horne, are almost certainly buried beneath the young alder trees north of the property.